Part 2 - Life in the Bush

I last time gave a very sketchy description

of my arrival as a 17yr old in the bush in the far North of NR,

at Kalungu , near the Tanganyika border.

I avoided going into any detail of our

life there but maybe I can expand a little on what was special

about that kind of existence for those who lived on the 'bush

stations' so had a certain degree of organisation around them.

shops, telephones, electricity supplies , running water etc and

yet considered themselves 'in the bush'.

We had none of those things, Food was

what we grew ourselves in the way of vegetables, eggs purchased

at one teaspoon of salt each, chickens at one shilling each, meat

I shot. We had some dehydrated vegetables in tins as a standby,

but they were awful. Dried powdered milk and bottles of 'camp

coffee' were the drink.

We had no refrigerator but found various

ways of preserving food. Our coldbox was a cabinet about 2ft cube

covered with mosquito netting and hessian was draped over it with

the lower edges in a reservoir of water. The water kept the hessian

wet and as it evaporated it cooled and kept the contents cool.

A variation on this was a double walled cabinet with charcoal

in the wall and when this was kept wet it cooled in the same way.

I tried several ways of preserving meat

for the times when no bloody fresh meat was available. We used

the biltong dried meat, hanging strips of meat treated with spices,

salt and pepper which was fine as biltong but could not be re-constituted

as meat for other dishes.

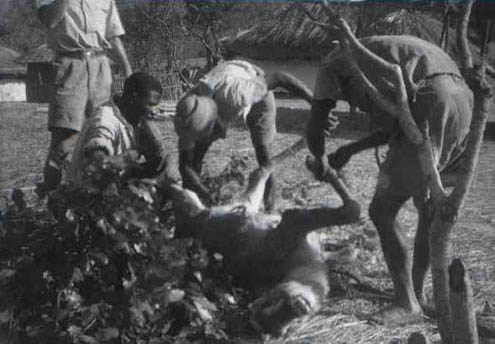

Bush Butchers

I used to take strips of this with me

when I went hunting and felt well nourished with it during a whole

day walking, sometimes covering as much as forty miles. I always

took a canvas 'water bag' which kept the water cool. My African

hunters would go a whole day without any food or water at all.

Bringing Home the Meat

I had 45 gallon drums filled with salt

water into which I put chunks of game meat which did not go rotten

but when soaked in fresh water and used in stews etc refused to

be anything other than tough, stringy, slimy bits of meat.

I sometimes resorted to night shooting

with a 'bulala lamp'. I got quite good at night hunting with my

.22 rifle with the aid of a torch strapped on my forehead, picking

out the reflected eyes of mainly duiker. The trick with night

shooting was to blacken the backsight with soot and shine up the

frontsight. The colour and size of each animals eyes was different

and usually could be relied on except that mistakes could be made.

I once shot at a leopard with the .22 thinking it was a reedbuck

and even more awful was my own dog, Jock (of the bushveldt) that

I mistook for a duiker!!

Jock with the leopard skin behind

him

I managed to keep a supply of fresh

meat for the camp most of the time but my Father kept me pretty

busy with him on the bridge.

While at Kalungu a leopard had attacked

our family dog one night. The dog escaped into the house but the

leopard came back every night. Twice I shot at it from the front

step of the house with the .303 and missed.

On the third occasion I used the .22

which I was more familiar with for night shooting. The following

day a villager brought in a leopard skin from an animal he found

in the bush nearby. It had just one small puncture in the neck

so I took it as my kill. Apart from a strip which I put around

my bush hat the skin hung around with us for years until dogs,

cats, insects etc reduced it to tatters.

I wonder if anyone still has a 'Saucepan

Radio'? I think they were always blue and were made using the

pressings of saucepans. They contained valves and the usual controls

and we could pick up Lusaka radio and ' Radio Club de Mocambique'.

I can't remember if we got 'The General Overseas Service of

the BBC'.

They were powered by a dry battery and

were wonderful. For most Africans they were their first encounters

with radios and when broadcasts were begun in some of the main

African languages a whole new world opened up for them.

Our music was from wind-up gramophone

using fibre needles and when they ran out we substituted acacia

thorns with no noticeable difference. Our evenings in the bush

playing Opera, symphonies and concertos etc on 78rpm records always

attracted listeners to the trees surrounding the camp. Whenever

any one of us stood up into view there was always a rustle of

movement in the trees around us as the spectators moved back out

of sight. I wonder what they thought of Beethoven and Verdi etc.

A gramophone recital audience

in the bush!

Communications were interesting. With

no telephone or radio contact, if we wanted to send messages anywhere

it had to be done from a boma and our nearest was Isoka, 30 miles

away. We used to send a runner, with a cleft stick. I don't know

why we did not send the truck (perhaps it was away collecting

things) but the message always got to the boma from where it was

sent on, by telegraph to headquarters. Our mail was brought once

a week by the Road Superintendent, Henry Walsh on his weekly tour

of the roads.

The construction methods for the bridge

were very primitive as I mentioned before. The scaffolding for

what was quite a large structure was made from bush poles cut

and brought on the heads of a very large number of local villagers,

men and women. The poles were tied together using ulushishi,

bark rope. The bark was stripped from the trees in long lengths

and soaked for a few days in the river to make it soften and pliable

enough to tie knots in it.

Scaffolding

If more flexible rope was needed the

bark was torn into thinner strips and then twisted in the same

way as ropes are made today so that each of three or four strands

was twisted in the opposite direction to its neighbour. This was

done mainly on the thighs of the workers. You might have observed

that Africans have very little body hair. I myself could not roll

rope or string on my thighs without suffering greatly as I 'plucked'

my hairy thighs.

We had one 14/10 diesel concrete mixer

to make all the concrete and no other mechanical aids. Concrete

was 'punned' by hand, no mechanical vibrators as in normal use

everywhere else and the constant stream of women and picannins

carried water for keeping the concrete damp and cool.

The only supplies received from 'line

of rail' at Broken Hill were the cement and reinforcing steel

which Thatcher and Hobson (which later became C.A.R.S.) delivered

in 30 ton loads. Everything else had to be found, created, invented,

adapted from what was available in the bush around us.

We were very sad when the bridge was

finished. It and our life there and the wonderful big bush house

had been our whole life for so long. Everything we had done and

learned had been totally new to us and the lessons learned influenced

nearly everything we did from then on.

We left the charming hardworking pleasant

Benamwanga tribe behind us and entered Wabemba country

but never forgot those interesting people.

Roy Williams